Dyslexia Guide

Dyslexia Guide: Technical Assistance for Providing Support for Students

“One thing we know for certain about dyslexia is that it is one small area of difficulty in a sea of strengths. Having trouble with reading does not mean that you’ll have trouble with everything. In fact, most children with dyslexia are very good at a lot of other things.”

—Dr. Sally Shaywitz, M.D., Overcoming Dyslexia, (2003)

The Nebraska Department of Education recognizes the importance of learning to read for students throughout the state. Understanding the specific needs of all students is paramount to providing appropriate instruction for children to progress in reading development.

Goals

- Develop an understanding of dyslexia.

- Understand the multifaceted process of assessment.

- Identify evidence-based practices that guide effective instruction and supports for children with characteristics of dyslexia.

- Provide educators and caregivers with information and resources regarding dyslexia.

- Provide clarification regarding the Nebraska Statute 79-11, 56-158.

Purpose

Dyslexia Guide: Technical Assistance for Providing Support for Students provides information, resources, guidance, and support to schools, families, and caregivers in understanding the specific learning disability of dyslexia. This guide includes additional resources for educators to access when they suspect a student may have dyslexia. Recognizing that Nebraska school districts have autonomy in selecting assessments, diagnostic tools, and instructional programs, the Nebraska Department of Education does not endorse any specific assessments or programs.

Information regarding implementing strategies according to the requirements of Nebraska Dyslexia Statute (79-11, 156-158), and how it relates to federal laws such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504), and the Nebraska Reading Improvement Act are also included.

For information on determining eligibility for students with a specific learning disability for the purpose of receiving specially designed instruction, please refer to the Office of Special Education’s Determining Special Education Eligibility for Specific Learning Disabilities.

This guide was developed to provide the most current resources, research, and documentation to support educators and guardians.

The Dyslexia Guide

“Reading is the fundamental skill upon which all formal education depends. Research now shows that a child who doesn’t learn the reading basics early is unlikely to learn them at all. Any child who doesn’t learn to read early and well will not easily master other skills and knowledge and is unlikely to ever flourish in school or life.”

—Moats. L.C. Reading is Rocket Science: What Expert Teachers of Reading Should Know and be Able to Do (1999)

Core Instruction

Core instruction is the first level of prevention and it should be the focus of instruction, providing a strong foundation. Students need to receive high quality instruction using evidence-based curriculum and instructional practices aligned to grade-level Nebraska State Standards. A key component of core instruction is the instructional materials aligned to state standards. The Nebraska Instructional Materials Collaborative highlights high quality, standards-aligned instructional materials and offers Nebraska-specific guidance documents to ensure materials meet the expectations of Nebraska’s Content Area Standards. Effective core curriculum and instruction within evidence-based core program should enable at least 80% of students to meet grade level reading standards. “Teaching reading is rocket science” (Moats, 1999). It requires strategic planning, guided by a scientific knowledge base.

During classroom instruction, a teacher implements the locally-determined curriculum, including instructional materials, and uses evidence-based teaching methods and strategies to engage students to support student learning of content area standards. Instruction is the way the curriculum is delivered to students. Core academic and behavioral programs provide a foundation for the use of evidence-based instruction. Core programs and curriculum materials that are aligned to standards and based in research, and that are integrated within the framework of a well-designed instructional model and implemented with fidelity, support student learning. The thoughtful use of evidence-based instruction and high-quality materials are key components in creating strong core instruction, increasing achievement, and decreasing the likelihood that some students will need targeted interventions. When selecting evidence-based instructional practices and strategies in the context of a high-quality curriculum and core instructional model, consider the following:

- Scope, sequence, and pacing of instruction

- Differentiated materials

- Alignment to Nebraska content area standards

- Opportunities for small, large-group, and individualized instruction

- Monitoring and evaluation of fidelity of implementation

- Professional development needs of teachers and building leaders.

The use of evidence-based instruction consists of a complex interaction between the curriculum, instructional materials, the classroom environment, and the needs of individual students. Therefore, context, purpose, and timing of such practices must be considered.

Evidence-Based Intervention

Interventions supported by higher levels of evidence, specifically “strong evidence” or “moderate evidence,” are more likely to improve student outcomes because they have been proven to be effective. When strong evidence or moderate evidence is not available, “promising evidence” may suggest that an intervention is worth exploring. The relevance of the evidence – specifically the setting (e.g., elementary school) and/or population (e.g., students with disabilities, English Learners) of the evidence – may predict how well an evidence-based intervention will work in a local context. State Education Agencies (SEA; e.g., Nebraska Department of Education) and Local Education Agencies (LEA; e.g., School Districts) should look for interventions supported by strong evidence or moderate evidence in a similar setting and/or population to the ones being served.

Under the Congressional Review Act, Congress has passed and the President has signed, a resolution of disapproval of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as amended by Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), accountability and State plans final regulations that were published on November 29, 2016 (81 FR 86076). This guidance document, Non-Regulatory Guidance: Using Evidence to Strengthen Education Investments, is unaffected by that resolution and remains applicable.

What are “Evidence-based” Practices?

Evidence-based practices (EBPs) are instructional techniques with meaningful research support that represent critical tools in bridging the research-to-practice gap and in improving student outcomes (e.g., Cook, Smith, & Tankersley, in press; Slavin, 2002 as cited by Cook & Cook, 2011). To be considered evidence- based, a practice must have multiple demonstrations of effectiveness for the population intended from high-quality experimental studies. Although a thorough explanation of how to determine if a practice is evidence-based is beyond the scope of this document, additional resources can be

found in the NeMTSS Frameworks Guide.

Implementation Fidelity

Implementation fidelity is defined as the degree to which a program or practices are implemented as intended by the developer, including the quality of the implementation. Consistency, accuracy, and integrity are factors that impact the degree of implementation fidelity.

In considering application of evidence-based practices in reading instruction, implementation fidelity becomes important because it: (1) ensures that reading instruction and practices are implemented as intended, (2) helps link student outcomes to delivery of instruction, (3) helps determine intervention effectiveness, and (4) helps in instructional decision-making.

Progress Monitoring

Once a district has determined which evidence-based curriculum, instruction and interventions to implement, they must pair materials with evidence-based assessment to continue to monitor student skill development and growth.

The schools problem-solving team uses progress monitoring or the repeated measurement of performance to determine whether student progress is adequate to meet the student’s instructional goal. If not, adjustments to the instructional program are made to meet the student’s needs.

Data-Based Problem Solving and Decision Making

Even with high quality, evidence-based core instruction, there will be some students who need additional supports to be successful behaviorally and/or academically. Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) leadership teams or other problem-solving teams should identify evidence-based intervention programs and practices; provide guidance around delivery and use of interventions, including matching intervention to student need; and, ensure a systematic process for monitoring intervention delivery and examining effectiveness of interventions for individuals and groups of students in order to plan for next steps (e.g., discontinuing intervention, continuing intervention as is, modifying intervention, intensifying intervention, or fading intervention). When considering the use of additional evidence-based interventions for students who need additional support and extensions from the core curriculum, districts need to consider how to identify and select evidence-based interventions that will:

- Establish a schedule of interventions

- Address the identified needs

- Provide professional development and coaching for staff to implement the intervention effectively

- Assess the fidelity of implementation as part of ongoing implementation

- Develop guidelines for intervention delivery

- Develop guidelines for documenting intervention delivery

- Develop guidelines for reviewing program-embedded intervention data

- Develop guidelines for intensifying interventions

If the team determines that the data led to the suspicion of a disability and that special education services are necessary to provide specially-designed instruction, the team must refer the student for an evaluation under IDEA. It is important to note that a student with dyslexia who is served through special education should receive instruction that is individualized to meet the student’s unique needs, including the needs identified due to dyslexia. For more information go to the NeMTSS, Data-Based Problem Solving and Decision Making document.

“Although it is helpful to agree upon a definition … it is more important to remember that no two … [individuals with dyslexia] are exactly alike, and that the manifestations of dyslexia change over time.”

—Moats, L.C. and Dakin, K.E., Basic Facts About Dyslexia & Other Reading Problems (2008)

Definition

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), the International Dyslexia Association (IDA), the Nebraska Dyslexia Association (NDA), and others have adopted and support the following definition:

Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and

by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede the growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.

Analysis of the Definition

Dyslexia is…

a specific learning disability

The term “specific learning disability,” as used here, is not meant to reference the same term that is used as a category for which a child may be found eligible for special education services. However, eligibility for such services may be considered on a case-by-case basis.

neurological in origin

The brain of a child with dyslexia is structurally and functionally different from the brain of a child who does not have dyslexia. These neurological differences may negatively impact abilities relating to phonological processing, rapid naming, word recognition, reading fluency, and reading comprehension (Shaywitz et al., 2006).

characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition

A child with dyslexia has difficulty with consistency in accurate word identification. Reading rate and expression may be negatively impacted, which may affect the skill of reading fluency, the ability to read quickly, accurately, and with good comprehension (National Reading Panel, 2000).

a deficit in spelling and decoding abilities

A child with dyslexia does not intuitively learn to decode and spell words. Therefore, direct, explicit, and systematic instruction in the application of phonics rules governing decoding and spelling is necessary for effective learning of printed language (Torgesen et al., 1999).

a deficit in the phonological component of language

Children with dyslexia have a core deficit in these phonological processing skills (Torgesen et al., 1996):

- Phonological awareness: This is usually the most pronounced deficit and refers to the understanding and awareness that spoken words consist of individual sounds (i.e., phonemes) and combinations of speech sounds (i.e., syllables and onset-rime units such as -ight, right, tight, etc.). Two important phonological awareness activities are blending (i.e., combining phonemes to form words) and segmenting (i.e., breaking spoken words down into separate and discrete sounds or phonemes.) Torgesen et al. (1997) relates that phonological awareness is more closely related to success in reading than is intelligence.

- Phonological memory: The ability to temporarily store bits of verbal information and retrieve it from short-term memory (Shaywitz, 2003).

- Rapid automatic naming (RAN): The ability to accurately and quickly retrieve the name of a letter, number, object, word, picture, etc., from long-term

memory. RAN is a skill predictive of efficacy in reading fluency, comprehension, and rate (Neuhaus et al., 2001).

often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities

A child with dyslexia exhibits reading difficulties despite demonstrated cognitive abilities in other areas. A key concept in dyslexia is an unexpected difficulty in reading in children who otherwise possess the intelligence, motivation, and reading instruction considered necessary for the development of accurate and fluent reading (Shaywitz, 2003).

reduced reading experience that can impede the growth of vocabulary and background knowledge

Lyon et al. (2003) highlight the impeded growth of vocabulary and background knowledge as a secondary consequence of dyslexia. Because a child with dyslexia does not read as much as his/her peers, word and background knowledge does not keep pace with expectations for age and grade level. Without adequate reading experiences, vocabulary development, background knowledge, and reading comprehension are ultimately impaired.

Characteristics of Dyslexia

Some of the most common characteristics associated with dyslexia are listed below. Not all students with dyslexia will exhibit all characteristics.

Attention

Students may have difficulty selecting and focusing attention on the most relevant stimuli essential for learning (Obrzut & Mahoney, 2011; Sinclair et al.,1984).

Language

Language delay and inappropriate use of language are problems some students may exhibit. Students may have problems in phonology (sounds), semantics (vocabulary), syntax (grammar), morphology (prefixes and suffixes), and pragmatics (social language).

Memory

Students may have deficits in memory, especially working memory. Working memory is the ability to temporarily hold and manipulate information for tasks performed daily.

Metacognition

The ability to adjust behavioral and environmental functioning in response to changing academic demands (Zimmerman, 1986). Metacognition also includes knowledge of the relationship between a task and strategy and when, where, and why a specific strategy is used (Reid & Lienemann, 2007).

Perception

Students may have difficulties recognizing, discriminating, and interpreting information (i.e., cognitive processes) through visual and auditory channels (Mammarella & Pazzaglia, 2010; Mercer & Pullen, 2009).

Processing Speed

Some students do not process information effectively and efficiently.

Social Emotional Learning

Some students with dyslexia have deficits in the area of social competence that are exhibited in a variety of social and emotional difficulties. They may misread social cues, be unaware of how their behaviors impact others, and may misinterpret the feelings of others.

Universal Screening & Early Identification

“Early screening is so important for our students with dyslexia…because it begins the process of quickly connecting students with the powerful

interventions that can help them overcome dyslexia, or even prevent it from ever being a factor of their lives.”

-Jan Hasbrouck, Conquering Dyslexia, (2020)

NeMTSS Framework and Early Screening for Dyslexia Identification

The Nebraska Multi-Tiered System of Support (NeMTSS) framework promotes an integrated system connecting general education and special education, along with all components of teaching and learning, into a high-quality, standards-based instruction and intervention system. This comprehensive and systematic approach is especially helpful for teaching struggling readers and learners from all social groups (Prestwich, 2014). Research shows the rapid growth of the brain and its responsiveness to instruction in the primary years make the time from birth to age eight a critical period for literacy development (Nevills & Wolfe, 2009).

Universal Screener for Reading

A universal screener for reading functions within the NeMTSS framework to support students’ reading success as a service provided through the Nebraska Reading Improvement Act (Section 79-2601- 79-2607). Following the NeMTSS best-practice model, school districts implement universal screening of reading for all students (K-3) at various points in the beginning, middle, and end of the school year, regardless of the student’s performance in the classroom. Universal screening focuses on specific skills that are highly correlated with broader measures of reading achievement resulting in the identification of those students potentially “at-risk” for future reading failure, including those with developmental reading disabilities. This information can also provide districts with information regarding the effectiveness of their core instructional program.

For K-3 students identified as “at-risk” based on an approved universal screener, an Individualized Reading Improvement Plan (IRIP) is created and implemented. This plan includes a supplemental reading intervention program with targeted system of supports that will accelerate literacy development. A supplemental reading intervention program is an intensive and research-based program of instructional strategies designed to support students in developing the critical skills associated with reading. Starting in fourth grade, school districts administer a statewide reading assessment to all students once a year. In addition, districts typically use benchmark assessments. These assessments can be used to help identify students who may be struggling readers.

If the indicators below are unexpected for an individual’s age, educational level, or cognitive ability, they may be risk factors associated with dyslexia. A student with dyslexia exhibits several of these indicators that persist over time and have a significant impact on his/her learning. A family history of dyslexia may be present. “Individuals can inherit this condition from a parent, and it affects the performance of the neurological system (specifically, the parts of the brain responsible for learning to read). It’s not uncommon for a child with dyslexia to have an immediate family member who also has this condition.

Also, it’s not unusual for two or more children in a family to have this type of learning disability ” (c.f. Schultz, 2008).

Potential Indicators of Dyslexia

This checklist is designed to aid educators in identifying students with characteristics or potential indicators of dyslexia and to document any skill deficits confirmed during screening to inform instruction. Check all areas of constant difficulty, based on observation, assessment, history, progress monitoring data, and work samples. It is likely that many students will exhibit some of the behaviors on this checklist. A preponderance of checks in one area suggests further examination into this set of skills.

Checklist for Potential Indicators of Dyslexia

Diagnostic Assessments

Diagnostic measures are formal and informal tools used to assess specific reading skills and behavior. They are typically administered for students for whom the universal screening process did not provide enough data to guide intervention planning or for students who have not been making expected progress in the current intervention and for whom more information is needed to guide next steps with instruction. Diagnostic assessments can be formal standardized tests of children’s component reading-and language abilities or can be informal measures such as criterion-referenced tests and informal reading inventories. Not all children need this kind of in-depth reading assessment, but diagnostic assessment is most important for struggling and at-risk

readers.

The results of diagnostic assessments can help identify specific skill-needs to match students to academic interventions and can help develop hypotheses about why problems may be occurring. Diagnostic assessments can determine appropriate lesson placement within intervention programs, can determine the appropriate level at which to set goals and monitor progress, and can inform the next steps for instruction and intervention. This information is documented on a student’s Individualized Reading Improvement Plan.

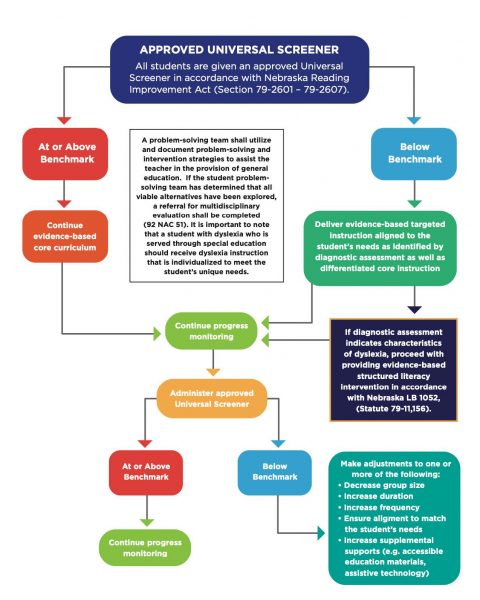

The Pathways for Identification and Support flowchart that follows in Figure 4.2 provides information regarding the decisions schools will make for each student as the school reviews data for reading risk. If data indicates characteristics of dyslexia, proceed with providing evidence-based structured literacy interventions in accordance with Nebraska Rev State Statute 79-11,156. A problem-solving team shall utilize and document problem solving and intervention strategies to assist the teacher in the provision of general education. If the student problem-solving team has determined that all viable alternatives have been explored, a referral for multidisciplinary evaluation shall be completed (92 NAC 51). It is important to note that a student with dyslexia who is served through special education should receive instruction that is individualized to meet the student’s unique needs, including the needs identified due to dyslexia.

Evaluation

When students continue to struggle with literacy skills, despite expert instruction, a formal evaluation is needed to determine whether the child meets the eligibility criteria for inclusion in special education and related services. The use of an MTSS/RTI process should not delay or deny an evaluation for dyslexia. Evaluation encompasses a variety of assessment activities including, but not limited to, observation and interview; screening and assessment; and formal testing by a professional trained in administering and interpreting psychometric results. A comprehensive assessment should provide the

documentation to determine eligibility under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), or the Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.

Decision Making for Eligibility of the Specific Learning Disability (SLD) – Dyslexia

This following table is not exhaustive, but rather a sampling of assessments and evaluations that may be considered as multiple data sources to assist and inform decision-making for eligibility of the specific learning disability (SLD): dyslexia.

Areas for Educational Evaluation

Components (If Applicable)

Assessments and Measures

Phonological Processing: The ability to analyze and break down spoken and written language into smaller components to use language effectively. Language can be broken down into words, syllables, and phonemes. Issues related to phonological processing are a main factor in dyslexia.

Phonological Awareness: The ability to discriminate and manipulate sounds within different levels of language including sentence, word, syllable,

and phoneme.

Phonological or Language-Based Memory: The ability to recall sounds, syllables, and words.

- easyCBM: Phoneme Segmenting (off grade level)

- Phonological Awareness Skills Screener (PASS)

- Comprehensive Tests of Phonological Processing-2nd

edition (CTOPP-2) - Phonological Awareness Test-2nd Edition (PAT-2)

- Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement Third Edition (KTEA-3) Phonological Processing

- Woodcock Johnson Reading Mastery Test

Rapid Automatic Naming: The ability to quickly name words, letters, symbols and objects.

N/A

- Comprehensive Tests of Phonological Processing-2nd Edition (CTOPP-2)

- Rapid Automatized Naming and Rapid Alternating Stimulus Tests (RAN/RAS)

- Woodcock Johnson Reading Mastery Test

Phonics Skills: The ability to understand the relationships between letters and sounds for written and oral language.

Sound-Symbol Recognition: The ability to recognize a connection between letters and their associated sounds.

- Phonics and Word Reading Survey (PWRS)

- Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement Third Edition (KTEA-3) LWR

- Woodcock Johnson Reading Mastery Test

Decoding: The ability to use symbol-sound recognition to analyze and decipher how to pronounce written words.

Decoding can be assessed using real words as well as words that are not real.

- easyCBM: Passage Reading Fluency (PRF) (on grade level, with error analysis)

- Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement Third Edition (KTEA-3) Nonsense Word Decoding and Decoding Fluency

- Phonics and Word Reading Survey (PWRS)

- Phonological Awareness Test-2nd Edition (PAT-2)

- Qualitative Reading Inventory-5th Edition (QRI-5)

- Test of Word Reading Efficiency-2nd Edition (TOWRE-2)

- Wechsler Individual Achievement Test – Third Edition (WIAT-III): Pseudoword Decoding Subtest

- Wechsler Individual Achievement Test – Third Edition (WIAT-III): Word Reading subtest

- Woodcock Johnson Reading Mastery Test

Receptive Vocabulary: The ability to understand words presented through auditory input

N/A

- Comprehensive Receptive and Expressive Vocabulary Test-3rd Edition (CREVT-3)

Oral Reading Fluency: The ability to accurately and fluently read connected text.

N/A

- Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test-4th Edition (ROWPVT-4)

Writing and Spelling

Writing and spelling can be assessed at both the sentence level and the paragraph level.

Encoding: The ability to decipher components of a word in order to spell auditory stimuli.

- Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fifth Edition (WISC-V): Vocabulary subtest

Information gleaned through a multidisciplinary evaluation will guide the multidisciplinary team’s decision in the determination of whether or not the student’s performance meets the set of outlined criteria enumerated in Nebraska Rule 51.

For students with dyslexia, in order to be eligible under the category of Specific Learning Disability, educational data must be used to demonstrate that the disability has a significant educational impact. Under IDEA (2006), to qualify for special education services in the category of specific learning disability, the child must have a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in an imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations. The category includes conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia.

The evaluation process analyzes data for the purpose of determining whether a student meets the criteria for different services. As a result of screening and subsequent evaluation, a student who is found to have dyslexia may receive an individualized reading improvement plan (K-3), be eligible for a 504 plan (to provide appropriate accommodations), or be found eligible for Special Education. The culmination of the evaluation process is a written report that includes evidence of whether or not specific criteria are met for eligibility, and clearly states recommendations for specially designed instruction, as mandated by federal law. The written report also lists accommodations such as providing additional time for assessments or having tests read to the student.

Use of the Term “Dyslexia” in Documentation

In October 2015, the federal Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS) published a Dear Colleague letter offering guidance to state and local agencies on the “unique educational needs of children with dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia” (OSERS, 2015). Although these conditions fall under the special education eligibility criteria of specific learning disabilities, the purpose of this letter was “to clarify that there is nothing in the IDEA that would prohibit the use of the terms dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia in IDEA evaluation, eligibility determinations, or IEP documents.”

The Dear Colleague letter also noted that “there could be situations where the child’s parents and the team of qualified professionals responsible for determining whether the child has a specific learning disability would find it helpful to include information about the specific condition (e.g., dyslexia) in documenting how that condition relates to the child’s eligibility determination.” The letter also says that “OSERS further encourages States to

review their policies, procedures, and practices to ensure that they do not prohibit the use of the terms dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia in evaluations, eligibility, and IEP documents.”

For additional resources on policy and practice considerations that can support the implementation of high-quality identification and evaluation, see SLD & Eligibility Under IDEA Resources to Improve Practices and Policy.

Individualized Reading Improvement Plan (IRIP)

An IRIP is focused on the interventions and supports for students who struggle with a particular aspect of reading. Like an IEP, the IRIP indicates performance levels on designated assessments; however, typically only on those that measure reading proficiency. While an IEP must be reviewed annually, IRIPs are designed to be in place for shorter periods of time as the student responds to interventions and gains proficiency. And though it is recommended that a team of school personnel that may include parents be involved in the process of creating an IRIP, the team will likely be smaller than that of an IEP team. Further, an IRIP will typically be a shorter, more concise document that requires less time to create and share. View additional information in the NDE IRIP Guidance Document.

Individualized Education Plan (IEP)

The Individualized Education Program (IEP) is defined as a written statement for each child or youth with a disability that describes their educational program and is developed, reviewed, revised, and implemented in accordance with special education laws and regulations. Each IEP is a vital document, for it spells out, among other things, the special education and related services each child or youth will receive. The Nebraska IEP Technical Assistance Guide outlines practical information, best practices, and the requirements of the IEP set forth through IDEA.

504 Plan

The American Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 impose broader eligibility standards than those of the IDEA. Therefore, a student not found eligible under the IDEA may still be eligible for special education or related services under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act or Title II of the ADA. Section 504 provides a broad spectrum of protections against discrimination on the basis of disability. For example, all qualified elementary and secondary public school students who meet the definition of an individual with a disability under Section 504 are entitled to receive regular or special education and related aids and services that are designed to meet their individual educational needs as adequately as the needs of students without disabilities are met. The U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (OCR) provides a complete resource guide, Parent and Educator Resource Guide to Section

504 in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools.

Intervention: A structured Literacy Framework for Struggling Readers

“Science has moved forward at a rapid pace so that we now possess the data to reliably define dyslexia, to know its prevalence, its cognitive basis, its symptoms and remarkably, where it lives in the brain and evidence-based interventions which can turn a sad, struggling child into not only a good

reader, but one who sees herself as a student with self-esteem and a fulfilling future.”

—Shaywitz, S.E. Testimony Before the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, (2014)

A Lens to Understand Reading

The Simple View of Reading

Gough and Tunmer (1986) proposed the Simple View of Reading to clarify the role of decoding in reading. Some educators believed that strong decoding skills are not necessary to achieve reading comprehension. Beginning and struggling readers were taught to compensate for weak decoding by guessing an unfamiliar word based on the first letter or the picture, then asking themselves if the word makes sense after reading the sentence. In contrast, when decoding is the focus of instruction, students are taught to sound out unfamiliar words using all the letters. (Farrell et al., 2010).

Decoding (D) x Language Comprehension (LC) = Reading Comprehension (RC)

The full article of The Simple View of Reading is available at The Center for Development and Learning. The Simple View formula makes clear that strong reading comprehension cannot occur unless both decoding skills and language comprehension abilities are strong.

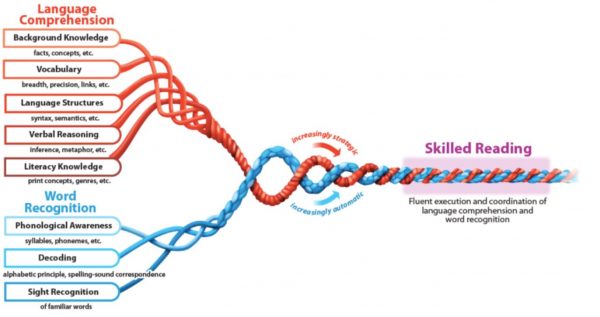

Scarborough’s Reading Rope

Hollis Scarborough, a leading researcher in literacy, expands the simple view of reading and shares that reading is a multifaceted skill that is gradually acquired through years of instruction and practice. Scarborough’s Reading Rope, (see Figure 5.1), illustrates how the many skills that are required to comprehend texts are intertwined and how they become more complex. Language comprehension skills become increasingly more strategic over time, while word recognition skills become increasingly more automatic. These skills enable a student to read connected text fluently and to coordinate word recognition and text comprehension. The strands weave together over many years and enable a student to become a skilled reader.

Reading as a Brain-Based Activity

As reading researchers became aware of the distinct skills that come together in the act of reading, they attempted to track the activity of the brain as it enacts the skills. The first images of the reading brain were created by Steve Petersen, Michael Posner, Marcus Raichle and colleagues in 1988, using positron emission tomography (PET) to view areas of increased blood flow when reading a word (Dehaene, 2009). Shortly thereafter, neuroscientists at various research centers began using Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scans while people read different prompts to observe areas of activation

when confronted by letters, words, non-words, rhyme, semantically related pairs, etc. (Shaywitz et al., 2000). Brain-imaging has supported the importance of phonology in reading, as well as the importance of visual recognition of orthographic patterns and, of course, semantic associations needed for comprehension (Dehaene, 2009). Understanding that reading is a brain-based activity that occurs in distinct locations in the brain has been important to our understanding of dyslexia. Researchers have especially investigated how the brain activation of readers with dyslexia differs from the activation patterns of non-impaired readers. For information on the brain-based sources of dyslexia, see Appendix B, “Brain-Based Sources of Dyslexia.”

Instructions for Students with Dyslexia

If, as a result of additional assessments, a child is found to have the characteristics of dyslexia, the Nebraska Dyslexia Statute states that the child shall be provided instruction that is systematic, sequential, and multisensory.

“Section 1. Beginning with the 2018-19 school year, unless otherwise provided in an individualized education plan for a student receiving special education services, each student who is identified as exhibiting characteristics of dyslexia shall receive evidence-based structured literacy instruction implemented with fidelity using a multisensory approach as provided in the technical assistance document for dyslexia adopted and promulgated by the State Department of Education pursuant to section 2 of this act.”

Structured literacy is an approach to reading instruction that is beneficial for both general education students at risk for reading difficulties due to a variety of factors (e.g., low socioeconomic status, status as an English learner(EL)) and for students with disabilities. This approach is characterized by the provision of systematic, explicit instruction that integrates listening, speaking, reading, and writing and emphasizes the structure of language across the speech sound system (phonology), the writing system (orthography), the structure of sentences (syntax), the meaningful parts of words (morphology), the

relationships among words (semantics), and the organization of spoken and written discourse.

The following fact sheet from The International Dyslexia Association, 2020, Structured Literacy: Effective Instruction for Students with Dyslexia and Related Reading Difficulties, (2020), describes the content of structured literacy (SL).

Content of Structured Literacy: Language

Dyslexia and most reading disorders originate with language processing weaknesses. Consequently, the content of instruction is analysis and production of language at all levels: sounds, spellings for sounds and syllables, patterns and conventions of the writing system, meaningful parts of words, sentences, paragraphs, and discourse within longer texts.

Phoneme Awareness

Becoming consciously aware of the individual speech sounds (phonemes) that make up words is a critical foundation for learning to read and spell. A phoneme is the smallest unit of speech that distinguishes one word from another. For example, the different vowel phonemes in mist, mast, must, and most create different words. Although linguists do not agree on the list of phonemes in English, it has approximately 43 phonemes–25 consonants and 18 vowels.

In preschool and early kindergarten, children typically learn the underpinnings for phonological awareness, including rhyming, counting spoken syllables, and reciting phrases beginning with the same sound. By the end of kindergarten, children should identify each speech sound by ear and be able to take apart and say the separate sounds of simple words with two and three sounds. More advanced phoneme awareness skills, especially important for spelling and reading fluency, include rapidly and accurately taking apart the sounds in spoken words (segmentation), putting together (blending) speech sound sequences, and leaving out (deleting) or substituting one sound for another to make a new word. These exercises are done orally, without print, and should be part of instruction until students are proficient readers. A large proportion of individuals with dyslexia have difficulty with this level of language analysis and needs prolonged practice to grasp it.

Phoneme awareness is an essential foundation for reading and writing with an alphabet. In an alphabetic writing system like English, letters and letter combinations represent phonemes. Decoding print is possible only if the reader can map print to speech efficiently; therefore, the elements of speech must be clearly and consciously identified in the reader’s mind.

Sound-Symbol (phoneme-grapheme) correspondences.

An alphabetic writing system like English represents phonemes with graphemes. Graphemes are letters (a, s, t, etc.) and letter combinations (th, ng, oa, ew, igh, etc.) that represent phonemes in print. The basic code for written words is the system of correspondences between phonemes and graphemes. This system is often referred to as the phonics code, the alphabetic code, or the written symbol system.

The correspondences between letters and speech sounds in English are more complex and variable than some languages such as Spanish or Italian. Nevertheless, the correspondences can be explained and taught through systematic, explicit, cumulative instruction that may take several years to complete.

Patterns and conventions of print (orthography)

Through explicit instruction and practice, students with dyslexia can be taught to understand and remember patterns of letter use in the writing system. For example, some spellings for consonant sounds, such as –ck, –tch, and –dge, are used only after short vowels. Some letters, like v and j, cannot be used at the ends of words. Only some letters are doubled. Some letters work to signal the sounds of other letters. These conventions can all be taught as part of the print system or orthography.

Print patterns and conventions exist as well for representing the vowel sounds in written syllables. It is a convention that almost every written syllable in English has a vowel grapheme. Structured literacy programs usually teach six basic types of written syllables: closed (com, mand), open (me, no), vowel-consonant-e (take, plete), vowel team (vow, mean), vowel-r combinations (car, port), and the final consonant-le pattern (lit-tle, humble). Recognizing written syllable patterns helps a reader divide longer words into readable chunks and helps in understanding spelling conventions such as doubling of consonant letters (little vs. title).

Morphology

A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning in a language. Morphemes include prefixes, roots, base words, and suffixes. These meaningful units are often spelled consistently even though pronunciation changes as they are combined into words (define, definition; nation, national; restore, restoration). Recognizing morphemes helps students figure out and remember the meanings of new words. In addition, knowledge of morphology is an aid for remembering spellings such as at-tract-ive and ex-press-ion.

Syntax

Syntax is the system for ordering words in sentences so that meaning can be communicated. The study of syntax includes understanding parts of speech and conventions of grammar and word use in sentences. Lessons include interpretation and formulation of simple, compound, and complex sentences, and work with both phrases and clauses in sentence construction.

Semantics

Semantics is the aspect of language concerned with meaning. Meaning is conveyed both by single words and by phrases and sentences. Comprehension of both oral and written language is developed by teaching word meanings (vocabulary), interpretation of phrases and sentences, and understanding of text organization.

Reading comprehension is a product of both word recognition and language comprehension. Throughout structured literacy instruction, students should be supported as they work with many kinds of texts—stories, informational text, poetry, drama, and so forth, even if that text is read aloud to students who cannot yet read it independently. Reading worthwhile texts that stimulate deep thinking is a critical component of structured literacy.

Principles and Methods of Structured Literacy Instruction

Structured Literacy is instruction that is explicit, systematic, cumulative, and multisensory. The International Dyslexia Association has published a knowledge and practice guide for teachers of reading. Standard 4 addresses Structured Literacy teaching, offering detailed guidance with regard to the nature of effective Structured Literacy in each major skill domain (phonological sensitivity and phoneme awareness, phonics and word recognition,

reading fluency, vocabulary, listening and reading comprehension, and written expression). Appendix C provides a list of Structured Literacy Knowledge Substandards as well as examples of best practices.

Explicit. In SL instruction, the teacher explains each concept directly and clearly, providing guided practice. Lessons embody instructional routines, for example, quick practice drills to build fluency, or the use of fingers to tap out sounds before spelling words. The student applies each new concept to reading and writing words and text, under direct supervision of the teacher who gives immediate feedback and guidance. Students are not expected to discover or intuit language concepts simply from exposure to language or reading.

Systematic and cumulative. In an SL approach, the teacher teaches language concepts systematically, explaining how each element fits into the whole. Instruction follows a planned scope and sequence of skills that progresses from easier to more difficult. One concept builds on another. The goal of systematic teaching is automatic and fluent application of language knowledge to reading for meaning.

Hands-on, engaging, and multimodal. Methods often include hands-on learning such as moving tiles into sound boxes as words are analyzed, using hand gestures to support memory for associations, building words with letter tiles, assembling sentences with words on cards, color-coding sentences in paragraphs, and so forth. Listening, speaking, reading, and writing are often paired with one another to foster multimodal language learning.

Diagnostic and responsive. The teacher uses student response patterns to adjust pacing, presentation, and amount of practice given within the lesson framework. The teacher monitors progress through observation and brief quizzes that measure retention of what has been taught.

Dyslexia Specific Intervention

For those students with persistent dyslexia, who need specialized instruction outside of the regular classroom, competent intervention from a specialist can lessen the impact of the disorder and help the student overcome and manage the most debilitating symptoms. The methods supported by research are explicit, systematic, cumulative, and multimodal in that they integrate listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

Resources included in this section should be considered as a representative sample of research/evidence-based materials and training that have been used successfully with students with dyslexia. While this list is intended to be useful to schools in selecting dyslexia-specific interventions/training, it does not constitute an endorsement by the NDE of any product or program.

Each of these dyslexia-specific interventions/programs is research/evidenced-based, providing specialized reading, writing, and spelling instruction that is multimodal in nature and that employs direct instruction of systematic and cumulative content. The sequence begins with the easiest and most basic elements and progresses methodically to more difficult material. Each step builds upon those already learned. Concepts are systematically reviewed to strengthen memory. The components of these dyslexiaspecific interventions and trainings include instruction targeting phonological awareness, sound-symbol association, syllable structure, morphology, syntax, and semantics.

Independent Teacher Training Programs

Accommodations

“For a dyslexic reader, accommodations represent the bridge that connects him to his strengths and, in the process, allows him to reach his potential. … Far and away the most crucial accommodation for the dyslexic reader is the provision of extra time. Dyslexia robs a person of time; accommodations return it.”

— Sally Shaywitz, M.D., Overcoming Dyslexia, (2003)

At the time when most students are developing coordinated literacy skills of reading, writing, and spelling, a student with dyslexia may struggle with these areas of skill development. Effective accommodations are aligned with classroom instruction; classroom assessments; and district and/or state testing. However, some accommodations appropriate for classroom use may not be considered appropriate in certain testing situations.

For NSCAS testing accommodations for students with disabilities, refer to NDE guidance at NSCAS Accommodations.

Classroom Accommodations

- Simplify and clarify directions – both oral and written

- Chunk assignments into smaller, more manageable tasks and provide a list of steps to complete these assignments

- Block extraneous stimuli

- Highlight essential information

- Allow extra time to process information including instructions as well as time to process answers

- Check for understanding. Assign a person to check in with this student each morning as well as at the end of the school day

- Reword as needed to ensure there is a clear understanding

- Preferential seating to allow monitoring of work and peer monitoring

Instruction

- Use multisensory instructional practices. Use systematic, explicit, direct instruction with use of visual aids and modeling

- Repeat directions – Use step-by-step instruction

- Provide a copy of lecture notes

- Review what was taught previously before teaching new skills

- Provide students with a graphic organizer or study guide with key terms and concepts

- Encourage use of mnemonic strategies

- Deepen learning through planned reviews

- Encourage use of a calendar

- Evaluate oral performance over written work

- Display work samples

Student Performance

- Plan altered response mode – oral or assignment substitutions

- Encourage peer-mediated learning/note sharing

- Provide additional practice

Testing

- Allow additional time on tests and avoid timed tests if possible

- Use match up, fill-in-the-blank, or short answer formats

- List vocabulary words for fill in the blank sections at the top of the page

- Allow oral testing

- Avoid multiple choice testing

- Offer small quizzes rather than one large test

- Alternate testing location in a quiet, distraction-free place

- Allow alternate access to the test through text-to-speech accommodations or human reader

- Refer to NSCAS Accommodations

Memory Supports

(Thorne, 2006)

- Give directions in multiple formats

- Teach students to over-learn material

- Teach students to use visual images and other memory strategies

- Give teacher-prepared handouts before class lectures

- Teach students to be active readers

- Write down steps in math problems

- Provide retrieval practice for students

- Help students develop cues when storing information

- Prime the memory before teaching/learning

- Review material before going to sleep

Reading

- Provide books on audio to help with comprehension

- Recorded Books

Spelling

- Allow the use of word banks or personal dictionary

- Present two possible spellings of a word and let the student choose the correct one

- Use word-prediction applications

- Use electronic spell-check applications

- Encourage the use of electronic dictionary

- Do not grade on spelling ~ grade on content only, not mechanics

- Accept letter reversals such as d and b, p and q, w and m.

- Allow extra time to complete spelling dictations such as spelling tests or sentence dictations

- Use a break-it-down routine to dictate words, such as repeat after me, say the sounds you hear, name the letters as you write. See Spelling and Students with Learning Disabilities.

Writing

- Provide visual frames such as lines on the paper or boxes for sentences to show where to write on the paper.

- Provide Popsicle sticks to space words.

- Use pencil-frames to encourage correct pencil grip

- Do not require copying from the book or the board

- Accept typed or dictated assignments

- Turn off spelling error feedback on word processing applications when drafting

- Provide speech-to-text technology tools

- Provide alternatives to written reports (create a video, posters, murals, class presentation etc.)

- Encourage students with dyslexia to turn in a draft early for feedback. Alternatively, give them an opportunity to revise their work (after receiving feedback) for a higher grade. For additional accommodations see Dyslexia Help.

- Encourage use of drawing to develop elaboration of content before writing

- Provide students with a graphic organizer or study guide with key terms and concepts

- Break the writing process down into small, sequential tasks

- Help students set goals for writing and mark off accomplishments on a check list

- Help students develop self-statements to encourage persistence when writing

- Use flexible work times. Students who work slowly can be given additional time to complete written assignments. Additional classroom strategies are listed in

Dyslexia In the Classroom, What Every Teacher Needs to Know.

Math

- Provide a list of steps required to solve problems

- Allow the use of manipulatives for helping to solve and/or model problems

- Find ways to create concrete representations when solving problems

- When story problems are given, read them out loud and check for understanding

- Use graph paper for alignment/organization

- Highlight steps in different colors

- Use or create worksheets with large print

- Offer extra time for tasks that require reading and writing

- Give access to voice-to-text technology

- Create or find worksheets with large amounts of space to write in

- Keep a number and letter strip on the student’s desk

- Provide sentence starters for open response questions

- Display samples of model work

- Allow the student to show alternate options for solving through a video or oral report

- Provide them with a calculator during class and tests

- Give them the option to record lectures

- Give them access to math apps and games that allow them to practice essential skills in a fun way

- Give them access to formula sheets, math fact charts, and tables

- Use technology that supports text-to-speech such as talking tape measures or talking scales

- Highlight keywords or numbers on word problems

Foreign Language

- Many schools will accept American Sign Language as fulfillment of their foreign language requirement. Since this is a visually based language, many dyslexic

students can master this language. - Dyslexia is a language processing disorder. A student who struggles in their native language due to dyslexia may also experience difficulty with a foreign language.

Assistive Technology and Accessible Materials

Definition

Assistive technology (AT) is defined as “any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of a child with a disability. The term does not include a medical device that is surgically implanted or the replacement of such device.” (34 CFR § 300.5). AT, in essence, can be understood as a tool or system of tools that allow students to successfully complete tasks that they may otherwise not be able to do (Parette et al., 2007). Students who may need AT are those with identified disabilities that are unable to meet the tasks and demands of curricular tasks and activities. For example, if a student is unable to decode text at an expected performance level and this difficulty is adversely impacting his/her/their ability to engage in grade-level tasks and activities, AT may be warranted.

A student is not simply given AT. AT must be embedded in a process that ensures that it is successful (Bowser et al., 2015). This process includes four main components: AT consideration, Provision of AT, AT implementation, and the Evaluation of the AT Effectiveness. Each of these components is explained in the table below.

The Assistive Technology Process

Component

Explanation

AT Consideration

An educational/IEP team determines whether or not the student needs AT through reviewing data related to a student’s current knowledge/skills, areas of difficulty, and curricular/IEP goals.

Provision of AT

If AT is determined to be necessary for a student to make progress, the team determines how the selected AT will be acquired, provided, and funded.

AT Implementation

The team ensures that the student can use the AT through determining what training needs to be provided, who needs the training and what supports need to be in place for the AT to be used effectively. Back-up plans are developed for when the AT malfunctions or is not accessible.

Evaluation of AT Effectiveness

The team engages in collecting data to determine if the AT a student is using is working, if a new AT tool/system is needed, or a student no longer needs the AT.

AT provided to a student outside the context of a well-executed process often results in the abandonment and discontinued use of that AT tools/system (Bowser et al., 2015; Johnston & Evans, 2005; Verza et al., 2006).

AT may serve as a viable solution when addressing the challenges that students with dyslexia may face (Reid et al., 2013). Specifically, research has shown that AT may provide benefits to students with dyslexia related to reading and writing (Dawson et al., 2019). Although not an exhaustive list, the table below presents some recommendations of potential areas in which AT may be considered for students with dyslexia.

Assistive Technology Considerations for Students with Dyslexia

Area

Recommendations

Reading

Text-to-speech tools and audio text may provide benefit to students with dyslexia who experience difficulty in decoding and fluency but have strong listening comprehension skills (Parr, 2013; Wood et al., 2017).

Using programs and devices (e.g., e-readers) to present text so that it appears in shorter lines with increased spacing along with highlighted key points may assist in reading comprehension and reading speed (Rello et al., 2014; Schneps, et al., 2013; Schneps, et al., 2013).

Writing and Spelling

Word processors and spell checkers may provide assistance in the areas of spelling, organization, and composition structure (Hetzroni & Shrieber, 2004; Hiscox et al., 2014).

Adding text-to-speech to word processing programs/apps allow students to hear what they are writing which may improve writing and spelling performance (Cullen et al., 2008; Higgins & Raskind, 2004).

Word prediction tools may help students improve overall spelling performance and increase the complexity of vocabulary chosen when writing (Evmenova et al., 2010; MacArthur, 1996).

Speech recognition programs may offer support in written productivity and accuracy (Higgins & Raskind, 1999; Quinlan, 2004).

For more information, visit the Learning Disabilities Association of America (LDA) webpage

Accessible Materials

Assistive technology provides one vehicle for providing students with the tools necessary for being successful in their learning. Learning experiences for students who have dyslexia – as well as all students – may be greatly enhanced by designing learning using the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL is a framework that allows educators to “improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn.” (CAST, 2020, para 1). The UDL Framework offers a set of guidelines that are based on designing learning through providing (1) multiple means of engagement; (2) multiple means of representation; and (3) multiple means of action and expression. To explore each of the guidelines, please link to an in depth exploration of the UDL Guidelines provides by CAST.

One of the central tenets of UDL is that learning should be designed with accessibility in mind. Accessible Educational Materials (AEM) are defined as materials and technologies usable for learning across the widest range of individual variability, regardless of format or features. Whether a material or technology is designed from the start to be accessible for all learners or is made accessible for learners with disabilities, it is considered AEM” (National Center on Accessible Educational Materials, n.d., para 1). Printed textbooks and instructional materials may present barriers for students and prevent them from accessing the curriculum inhibiting their learning. Similarly, digital materials and other educational technologies may not be designed to allow students with a wide range of needs to effectively access and use them. These statements may apply to students with dyslexia. For example, if a student is unable to read grade-level materials or access technologies that are part of the learning experience due to dyslexia, the student would experience greater difficulty and barriers in keeping up with curricular content. If materials and technologies provided to students for use in learning experiences are accessible from the beginning (i.e., AEM), then students with dyslexia would experience fewer barriers in engaging in their learning.

The easiest way to ensure access to AEM is to purchase accessible instructional materials and technologies. The United States Department of Education Office for Civil Rights notes that instructional materials and technologies are accessible when a learner with a disability “is afforded the opportunity to acquire the same information, engage in the same interactions, and enjoy the same services as a learner without a disability in an equally effective and equally integrated manner, with substantially equivalent ease of use.” The National Center on Accessible Educational Materials offers guidance to

schools and families on how to acquire AEM for students.

In Nebraska, students with dyslexia who have an IEP or a 504 Plan may access additional services. Bookshare.org is a service that provides access to accessible digital versions (e.g., audio text, digital text) of textbooks and trade books. The service is free to students who receive special education services and have a qualifying print disability certified by a qualified professional. Learning Ally is another service that provides audio and digital text of textbooks and trade books. This service is a subscription-based services available to students that have a qualifying print disability certified by a qualified professional. Finally, the Nebraska Library Commission Talking Book and Braille Service may be a service for accessing accessible materials as well. Keep in mind that AEM often need to be paired with an assistive technology (e.g., a text-to-speech app on a mobile or computer device) for a student to use them.

CAST and the National Center for Accessible Education Materials offers a tool to help educators and families make decisions about the need for and the nature of potential AEM to help individual students. This tool is called the AEM Navigator. The AEM Navigator takes teams through a four-point decision making process focusing on (1) the determination of need, (2) selection of format(s), (3) acquisition of formats, and (4) selection of supports for use. Another tool offered by CAST and the National Center for Accessible Education Materials is the AEM Explorer. The AEM Explorer is a free downloadable simulation tool that allows exploration of different features of potential assistive technologies (e.g., magnification, colors of text, human/computer generated text to speech, text highlighting) to help students, families, and education teams to determine the features needed by the student. Don Johnston offers an assessment tool called Protocol for the Accommodations of Reading (PAR) that helps to create a systematic process for making determinations about different reading accommodations (including the use of AEM and assistive technologies) needed for individual students. This tool is free for individual use.

Family Resources

Reading does not develop naturally like seeing, hearing, and speaking. Rather, it happens very intentionally when specific skills are taught, practiced, and learned in a highly prescribed sequence that focuses on principles of printed language. To master the reading process a child must learn about: a) the world of letters; b) letters that make specific sounds; c) individual and discreet sounds (called phonemes) that are synthesized (blended) into words, both regular and irregular, and their word families; and d) words that have specific meanings (called vocabulary) that come together to express concepts.

Early identification is the key! If a child has trouble reading in the early grades, parents and teachers are more likely to detect the problem and initiate assessment, evaluation, and programming that provide the elements of effective teaching to ensure a greater level of reading success for students with dyslexia.

As a parent of a child with dyslexia, you may find the following suggestions helpful:

- Learn about dyslexia.

- Talk with your child about dyslexia.

- Embrace your child’s natural intelligence.

- Provide positive feedback and encouragement.

- Collaborate with educators.

- Read aloud daily!

- Encourage reading and writing – independent reading time.

- Assist with homework. Monitor self-esteem.

A-B

504 Plan: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in programs and activities that receive federal financial assistance from the U.S. Department of Education. A plan developed under this legislation includes accommodations that the student needs for equal access to instruction and assessment. It protects students who are not also protected by special education law, IDEA.

Academic vocabulary: Words traditionally used in academic dialogue and text. Accommodations: Accommodations are practices and procedures in the areas of 1) presentation, 2) response, and 3) setting/timing/scheduling that provide equitable access during instruction and assessments for students with disabilities. Accommodations are intended to reduce or even eliminate the effects of a student’s disability; they do not reduce learning expectations.

Accuracy: The ability to recognize words correctly.

ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. ADHD is a medical condition that impacts learning through chronic and serious inattentiveness; hyperactivity and/or impulsivity; and excessive motor behaviors that impede learning.

AEM: Accessible Education Materials

Alphabetic Principle: The understanding that the sequence of letters in written words represents the sequence of sound (e.g., phonemes) in spoken words.

Assistive Technology: Any item, piece of equipment, or product system that is used to increase, maintain, or improve functional capacities of a child with a disability.

Automaticity: The ability to do things without intense concentration. Automaticity is the result of learning, repetition, and practice that allows an individual to perform tasks rapidly and effortlessly without attention (e.g., as an “automatic” process). In reading, automaticity is the rapid, effortless word recognition that comes from reading practice.

Background knowledge: Connections formed between the text and the information and experiences of the reader.

Benchmark: Pre-determined level of performance on a screening test that is considered representative of proficiency or mastery of a certain set of skills.

C-D

Classification accuracy: Extent to which a screening tool is able to accurately classify students into “at risk” and “not at risk” categories.

Connected text: Words that are linked as in sentences, phrases, and paragraphs.

Controlled text: Reading materials in which a high percentage of words can be identified using their most common sounds and use sound-letter correspondences that students have been taught.

Core Instruction: Those instructional strategies that are used routinely with all students in a general educational setting.

Cumulative: Each step is based on concepts previously learned.

Decoding: Process of using sound-letter correspondences to sound out words or nonsense words.

Diagnostic: Formal and informal tools used to assess specific reading skills and behavior.

Dyscalculia: A term used to describe certain learning disabilities that affects a child’s ability to understand, learn, and perform math and number-based operations. https://childmind.org/article/how-to-spot-dyscalculia/

Dysgraphia: A brain-based learning disability that affects fine motor skills used in writing and which leads to impaired written expression.

Dyslexia: A specific learning disability that is neurological in origin.

E-G

Encoding: Encoding is a process of translating spoken language into written symbols – that is, spelling. Encoding means attempting to write letters to represent sounds in words. Spelling conventions and patterns should be taught as they are needed to spell words that the student is learning to decode.

Evidence-based practices: A particular approach, a specific strategy, or an instructional method which has had a record of success. There is reliable, trustworthy, and valid evidence to suggest that when this instruction is used with a particular group of children, the children can be expected to make adequate gains in reading achievement. Sometimes the terms “research-based instruction” or “scientifically based research” can be used to express the same idea (International Reading Association, 2002).

Explicit instruction: Direct, structured, systematic approach to teaching that includes both instructional design and delivery procedures.

Expressive language: Language that is spoken. Fidelity of implementation: The degree to which instruction follows the intent and design

of the program.

Fluency: In the reading process, fluency is the ability to read text accurately, quickly, and with appropriate expression and prosody (e.g., rhythm, intonation, and phrasing). Fluency provides the bridge between word recognition and reading comprehension. It involves accurate anticipation of what will come next in the reading of text.

Grapheme: Letter or letter combination that corresponds to a single phoneme. Guided practice: Approach in which students practice newly learned skills with the teacher providing prompts and feedback.

H-N

High frequency words: Small group of words (300-500) that account for a large percentage of the words in print. They can be phonically regular or irregular.

Individualized Education Program (IEP): A legal written document outlined by IDEA that states the disabled child’s goals, objectives and services for students receiving special education. It states any accommodations, modifications, and supplementary aids the student will receive.

Individualized Reading Improvement Plan: Any child in Nebraska with characteristics of dyslexia should receive an Individualized Reading Improvement Plan per the Nebraska Dyslexia Statute which ensures students have the necessary support to read proficiently by grade 3.

IQ-discrepancy approach: An approach to assessment that looks at whether there is a significant difference between a student’s scores on a test of general intelligence and scores obtained on an achievement test; also called severe discrepancy model.

MTSS Leadership Teams: Multi-Tiered Systems of Support – Collaboration among members of a team that helps educators provide academic and behavioral strategies for students with various needs.

Metacognitive skills: Strategies that help students to “think about their thinking” before, during, and after they read.

Modifications: Modifications refer to practices that change or reduce learning expectations and content.

Morphology: A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning in language. Studying base elements and affixes helps readers decode and unlock the meanings of complex words.

Multisensory teaching: The use of visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile modalities for enhancing memory and learning in students with dyslexia.

Nonsense words: Pronounceable letter patterns that are not real words; also called pseudo words.

Norm: Standard of performance on a test that is derived by administering the test to a large sample of students.

O-P

Orthography: The written system for any language.

Orthographic Awareness: The brain-based ability to process written language at the word level.

Phoneme: The smallest parts of sound in a spoken word that make a difference in a word’s meaning. The English language has about 44 phonemes. When phonemes are combined, they make words. For example, the word bat has 3 phonemes: /b/, / a/, /t/.

Phonemic awareness: Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. Before children learn to read print, they need to be aware of how the sounds in words work. They must understand that words are made up of speech sounds, or phonemes (the smallest parts of sound in a spoken word that make a difference in a word’s meaning).

Phonics: A method for teaching reading and writing by developing the learner’s phonemic awareness—the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate phonemes—in order to teach the correspondence between these sounds and the spelling patterns (graphemes) that represent them. The goal of phonics instruction is to enable beginning readers to decode new written words by sounding them out, or in phonics terms, blending the sound-spelling patterns.

Phonological awareness: The sensitivity to, or explicit understanding of, the sound structure of spoken words and the ability to hear sounds that make up words in the spoken language. This includes recognizing words that rhyme, determining whether words begin or end with the same sound(s), understanding that sounds can be manipulated to create new words, and separating words into their individual sounds.

Phonology: Study of sound structure of spoken words.

Psychometric Results: Results from tests designed to measure different mental traits, personality characteristics, abilities, and cognitive processes.

R-Z

Rapid Automatic Naming: The ability to efficiently retrieve phonological information (individual sounds in words, pronunciations of common word parts, pronunciation of whole words) from long-term memory. Strength in RAN is predictive of efficient reading rate and fluency. RAN is highly correlated with success in reading.

Receptive language: The ability to accurately understand written and spoken information.

Semantics: The meaning of a word, a phrase, a sentence or text.

Sound-Symbol Association: Once students develop phoneme awareness, they must learn the alphabetic principle – how to map phonemes to letters (graphemes) and vice versa.

Structured Literacy: Explicit teaching of systematic word-identification/decoding strategies. These benefit most students and are vital for those with dyslexia.

Syllables: A syllable is a word or part of a word with one vowel sound. There are six types of syllable: closed (nip), open (no), vowel-consonant-e (note), vowel team (need), vowel-r (nerd), and final stable syllable (nibble).

Syntax: The set of principles that dictate the sequence and function of words in a sentence – includes grammar, sentence structure, and the mechanics of language.

Systematic: Organization of material that follows the logical order of language. The sequence begins with the easiest and most basic concepts and elements and progresses methodically to the more difficult.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL): A set of principles for curriculum development and instructional planning that gives all students equal opportunities to learn.

Working memory: The ability to hold in mind and mentally manipulate bits of information over short periods of time. It is often thought of as a mental workspace that used to store information. It may involve new or already stored information and is important for learning, reasoning, and comprehension

More Dyslexia Information

Brain-Based Sources of Dyslexia

Judith K. Wilson, Ph. D.